Alade v. the Federal Republic of Nigeria

Nearly a Decade in Pretrial Detention

Police in Nigeria routinely charge suspects with a serious offense in order to have them detained, but make little or no effort to investigate or prosecute the case. As of October 2012, 38,352 persons or 71% of the prison population were detained awaiting uncertain trial. Regrettably, the percentage of pretrial detainees as a proportion of the prison population has been stable over the last two decades. In 2006, the Nigerian Prisons Service reported that the average period of pre-trial detention in Nigeria was nearly four years, with many held for longer. Sikuru Alade was held in pretrial custody for more than nine years without being tried. The Community Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) found that this violated the prohibition of arbitrary detention in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

Facts

Sikiru Alade was born in Nigeria in 1975. He was self-employed as a panel beater in Lagos before his arrest. On or about March 9, 2003, Alade was arrested near the old Lagos toll gate area by a plain clothes police officer, who neither disclosed his identity nor gave any reasons for the arrest. The policeman then forcefully dragged Alade to the Ketu Police Station in Lagos State, where he was detained.

On May 15, 2003, he was brought before the Magistrates’ Court in Yaba, Lagos State, on an allegation of armed robbery under the procedure known as the “holding charge,” a process by which a suspect is brought before a magistrates’ court that lacks jurisdiction over the offense for which the suspect has been detained. The magistrate therefore cannot order his release, and has no option under the law but to remand him in custody on the basis of a holding charge, without any determination whether there are sufficient grounds for detention.

Pursuant to the holding charge, on May 15, 2003, a magistrate ordered Alade to be remanded in custody. He was then held at the Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison in Apapa, Lagos, for more than nine years without being returned to court, or charged with a crime under any law before any court of competent jurisdiction. On September 18, 2012, following the judgment of the ECOWAS Court, he was released following a review by the Chief Judge of Lagos.

Section 35 of Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution states that the police may not detain any suspect for longer than 48 hours without a court order. The initial detention of Alade from March 9 until May 15, 2003 was not authorized by any court of law, and was thus unlawful.

The holding charge compels the indefinite detention of suspects without charge, sufficient evidence, or due process, but was upheld by the Supreme Court of Nigeria in March 2007.

Over 70 per cent of Nigeria’s prison population consists of pretrial detainees, and nearly a quarter of them have been held for at least one year, reflecting both an overburdened justice system and structural problems between Nigeria’s state and federal justice systems.

The problem is not restricted to Nigeria. In West Africa, five other countries shared the distinction of having more than half their prison population constituted by pretrial detainees in September 2012. Remarkably, four of those countries—Benin, Liberia, Niger, and Nigeria—were among the top ten worldwide with the highest pretrial detainee populations.

Open Society Justice Initiative Involvement

The Justice Initiative, together with co-counsel Mutiu Ganiyu, sought to review the use of the holding charge to justify indefinite pre-trial detention through a legal challenge brought on behalf of Alade to the Community Court of Justice of ECOWAS.

Arguments

Arbitrary detention. The use of the holding charge to detain a suspect indefinitely violates Alade’s rights under the African Charter to liberty and freedom from arbitrary detention (Article 6), to have his cause heard within a reasonable time (Article 7), and to equality before the law (Article 3).

Power to release. International human rights law requires that a suspect is promptly brought before a judicial officer who has the power to order release. The police frequently use a holding charge to bring a suspect before a magistrate who does not have such a power.

Lack of fixed return date. Human rights law requires that any remand in custody is for the shortest possible time. When a magistrate remands a suspect in custody on the basis of a "holding charge" it is often done without a fixed return date for the next hearing, allowing the case to be forgotten. Even where the magistrate does order a return date, the police often fail to produce the detained person on that date.

Lack of reasons. A judge must give reasons when remanding an individual in custody, identifying the grounds upon which custody is ordered, such as fear of flight, interference with witnesses or evidence, prevention of further offenses, or the protection of public order. A magistrate remanding an individual in custody on the basis of a holding charge does not give any reasons for denying provisional release, save to assert lack of trial jurisdiction.

Special diligence. Human rights law requires the prosecution authorities to demonstrate that they have acted with "special diligence" in preparing the case, so as to keep pre-trial detention to a minimum. However, the facts of this case suggest that police officers in Nigeria routinely arrest before investigation, which often takes years to complete.

Sufficiency of evidence. Police officers routinely arrest without sufficient evidence to remand, which should amount to "reasonable grounds" or "grounded suspicion" needed to justify a remand in custody.

In its judgment of June 11, 2012, the ECOWAS Court found that the prolonged detention of Alade was unlawful, and violated both the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the 2005 ECOWAS Protocol.

Jurisdiction. The government of Nigeria submitted that Alade had failed to approach a national court to seek his release from custody, that he had failed to exhaust domestic remedies.The court disagreed, and found that the claim fell within Article 9(4) of the ECOWAS Protocol which provides that “The Court has jurisdiction to determine cases of violation of human rights that occur in any member state.” Here, Alade’s detention fell within Article 6 of the African Charter (right to liberty and security of the person) and thus fell within the jurisdiction of the Protocol.

Fourth Instance. Nigeria argued that the court was improperly acting as an appellate court from the decision of the magistrate. The ECOWAS Court emphasized that there was a “thin line of not reviewing the decision but hearing the matters that flow from the decision,” and that in this case they were reviewing the fact that the applicant was held without trial upon a holding charge, rather than reviewing the detention order itself. The violation of human rights that arose from that order fell within the protocol and was thus a matter for the court.

Burden of Proof. The government of Nigeria had initially denied that they had Alade in their custody, and “argued vehemently” that it was for the plaintiff to prove that he was detained. The court found that “every material allegation of the claim must be justified by credible evidence and the defence should also sufficiently satisfy every defence and put forward that would rebut the claim.” Here, the plaintiff had served the Deputy Comptroller of Prisons with a notice to produce Alade’s detention warrant, but it was not produced. The court concluded that “it would be deduced that the withholding of the warrant is indicative of the fact that the same would have been unfavorable if produced.”

Right to Liberty. The court concluded that “where deprivation of liberty continues for some time, the grounds that originally warranted detention may subsequently cease to exist. Here, “even though the original detention was by a competent court, the Magistrate court on a holding charge … was not competent to try the allegation… and the holding charged ceased to be effective in law because of that influx of time”. The court further held that the purpose of the detention was relevant to whether or not the detention was unlawful, finding that “it is the position in law that the said process was not meant to keep the plaintiff perpetually in custody but to be tried by an appropriate court thereby making the process legal and competent.” The court concluded that “No court would allow such prolonged detention to continue without abating same. For that reason, the said detention is hereby adjudged illegal and this Court holds that the plaintiff has satisfied the requirements of proof …that his human right was violated.”

Damages. The court concluded that damages should be awarded in order to “place the claimant in the position he/she would have been, had the friction complained of not taken place”. The Court ordered compensation of 300,000 Naira for each of the nine years that he had been detained, a total of 2,700,000 Naira (approximately $17,000 USD).

Release. The court found that as the plaintiff “was entitled to the relief sought including that of his discharge/release from Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison forthwith, and this court so orders. The applicant is hereby discharged from detention accordingly.”

Alade released from detention by the Chief Judge of Lagos.

ECOWAS Court finds a violation of the African Charter.

Hearing before the ECOWAS Court.

Amended application submitted to the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice.

Alade first taken into police custody at Ketu Police Station, Lagos.

Alade appears before the Yaba Magistrates’ Court, Lagos, his only court appearance. He is detained at the Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison.

Related Work

ECOWAS Community Court of Justice

Learn more about the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Community Court of Justice, which has accepted the submission of individual complaints for human rights violations since 2005.

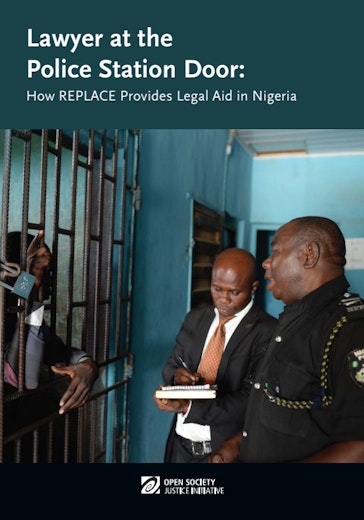

Lawyer at the Police Station Door: How REPLACE Provides Legal Aid in Nigeria

This 12-page illustrated brochure summarizes the successes achieved by a project that used duty solicitors to give detainees in Nigerian police stations early access to legal advice.

Making Legal Aid Work in Nigeria’s Police Stations

Eighty percent of Nigeria’s prison population is awaiting trial. But young lawyers posted at local police stations are now keeping more people out of unnecessary detention.

Innovative Efforts, Proven Results: How Timap for Justice Provides Legal Aid in Sierra Leone

This 12-page illustrated brochure summarizes the successes achieved by a community paralegal project in Sierra Leone that focused on providing front-line legal aid to pretrial detainees.