An Ongoing Syrian War Crimes Trial Provides Important Lessons about Witness Protection

By Eric Witte & Irmina Pacho

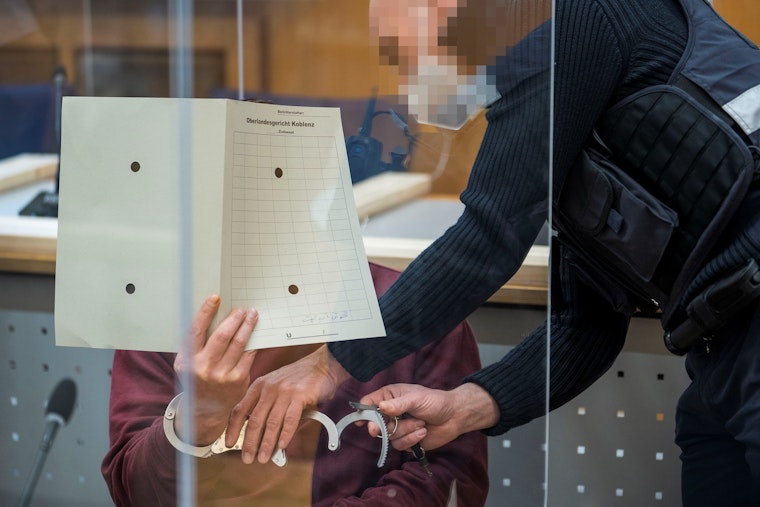

On February 24, a German court convicted former Syrian intelligence official Eyad al-Gharib for aiding and abetting a crime against humanity involving the torture of dozens of Syrian civilians detained after participating in a democratic uprising. For the first time, a court has held a former Syrian government official criminally accountable for torture—a milestone verdict only possible due to crucial witness testimony.

While many hailed the verdict as the “beginning of justice” for crimes against humanity during the Syrian war, it came at a significant cost to some of the witnesses who made the prosecution possible. Some witnesses—and individuals who chose not to travel to Germany to testify—faced intimidation, raising a critical question: Can national justice systems in Europe ensure the safety of witnesses to grave crimes who make such convictions possible?

In Germany, a search for answers is urgent, because the trial of Anwar Raslan, a more senior Syrian official, continues and the country is now the “go-to” jurisdiction for future Syria atrocity trials. The trial against al-Gharib originally began jointly with that of Raslan. Prosecutors say Raslan is responsible for a number of war crimes that dwarf those for which al-Gharib was convicted, including the torture and abuse of more than 4,000 detainees, 58 related murders, and rape and aggravated sexual assault, all while leading Branch 251 of Syria’s General Intelligence Division, where al-Gharib worked. Now that al-Gharib has been convicted, the trial against Raslan continues independently.

The harassment and serious intimidation that witnesses have faced is just a precursor to what they risk in testifying against this major suspect. In Raslan’s trial, numerous victims have taken the stand and recounted traumatic experiences of torture. Former Syrian government officials also have implicated the two defendants, providing details of the systematic torture used to suppress popular dissent against President Bashar al-Assad. Some witnesses, facing threats from Syrian intelligence services and supporters of the accused, expressed surprise at being called to testify. Some had come to prosecutors’ attention through the work of civil society organizations, including the Justice Initiative and the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, who took measures to help them understand their risks and rights. Other witnesses were referred to prosecutors by German immigration authorities responsible for processing asylum applications and often were not aware of the process or their rights.

Because their presence was required under German law, they had no choice but to appear. Judges and prosecutors have been reluctant to allow them to testify anonymously, fearing such testimony weakens witness credibility. Germany does offer relocation through a witness protection program for residents and their families, but the threshold for acceptance is high. And for people outside Germany—including many witnesses in the al-Gharib and Raslan cases—the justice system can take only minimal steps to provide protection. Family members in Syria are on their own.

It doesn’t have to be this way. While taking account of the fair trial rights of the accused, international tribunals, such as the International Criminal Court, allow for in-camera proceedings not open to the public and can order protection of a victim’s identity through pseudonyms, visual or acoustic distortion, remote testimony, or even total anonymity. Individual countries with extensive experience with domestic trials for grave human rights violations and complex crimes, such as Colombia, have also made strides in ensuring witness protection through such measures.

Even if Germany adopted such reforms, however, inherent challenges would persist. How can a country protect witnesses beyond its borders? What’s more, the patchwork of domestic laws across countries that allow them to prosecute grave crimes under the legal principle of universal jurisdiction means there is no common prosecutorial or judicial strategy among jurisdictions. One country’s war crimes suspect may be another’s coveted insider witness.

But in the absence of greater international cooperation or a treaty-based international tribunal for Syria, these universal jurisdiction prosecutions are the world’s best hope for accountability in the Syrian war. By devoting significant resources to providing a measure of justice for Syrian victims, Germany, France, Sweden, and other countries are filling a void left by Russian and Chinese obstruction of Syrian accountability measures at the UN Security Council.

This leadership deserves praise. At the same time, states must do more to protect vulnerable victims and witnesses. While protecting witnesses is a fundamental requirement of the fair administration of justice everywhere, Germany and other states applying universal jurisdiction are also obligated under domestic and international law to do so. Under a European Union directive, member states must ensure that victims receive the information, support, and protection necessary to participate in criminal proceedings. Lawmakers must examine domestic reforms to help those who risk so much in taking the witness stand to reveal details about some of the worst crimes of our time.

Eric Witte is the senior project manager on national trials of grave crimes for the Open Society Justice Initiative.

Irmina Pacho is an associate legal officer with the Open Society Justice Initiative.