Q&A: Using the Law to Confront Poverty in India

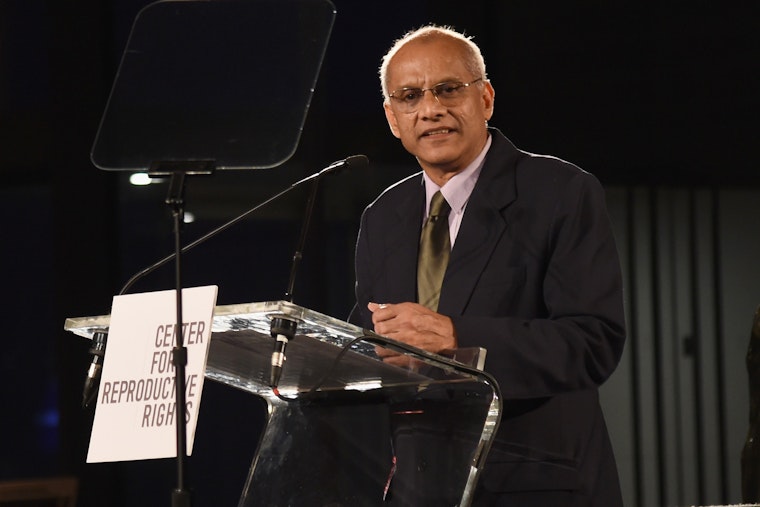

Colin Gonsalves is a leading Indian human rights lawyer, and founder of the Human Rights Law Network. With legal aid centers in several parts of India, HRLN is one of the foremost organizations in India working on access to justice for marginalized individuals and communities. Gonsalves spoke recently in Berlin with James A. Goldston, executive director of the Open Society Justice Initiative, about his story, and his achievements.

Goldston: You are an iconic figure not only in India, but also around the world for the social change you have helped achieve. You did not start out as a lawyer, is that right?

Gonsalves: Right. I graduated as a civil engineer in 1975. I was very unhappy with civil engineering and I left to join social movements. I first joined the housing rights movement, fighting against evictions. Then I met a trade unionist, who was my guru. Everyone has a guru in their lives: one person who changes their lives forever. He taught me to see the world’s problems and questions through the eyes of working-class people. Even though I spend a lot of time in the courts, it is important to know the shortcomings of the courts, and where to use struggle and where to use the courts. I have quite a finessed understanding of the balance, and I use that reasonably well in my work.

Goldston: You have been involved in so many landmark cases in India, including the right to food. Can you tell us about that case?

Gonsalves: In 2000, I was in Jaipur, Rajasthan, when I heard about starvation reports. We went to the homes of the people who had died, and you could see there was grain lying outside of what we call the godowns, and it had rotted in the rains. The rats were eating the grain. Not due to the monsoon or anything like that. The government decided it would no longer subsidize grain for its people. It was starvation by design, not by accident.

So, we said, why don’t we file a case on Rajasthan. It was a very simple case, really. I was a new lawyer, and new to the Supreme Court. I was terrified of the consequences of the case being dismissed. It came before a Chief Justice who had no love for human rights at all. As I stood before the court wondering what this guy is going to say, he looked up at me and said, “This cannot be. Make this case for the whole country, Mr. Gonsalves, and not just for the state of Rajastan.” And then he really took off. It became the judge’s case, as well. We eventually amended the petition and made all 25 states in India parties to the petition. The power of public interest litigation is extraordinary—a simple public interest petition in one state case became a national case, and with very little money.

Goldston: What was the outcome of the ruling?

Gonsalves: Well, it was not like a traditional judgment. It came in pieces. It is what we call a continuing mandamus, where it stays before the court. It came in the series of 40 orders [requiring government action]: one order relating to supplementary nutrition, to the mid-day meal, the right to work, homeless people on pavements who died during winter because they were starving and had very low resistance.

Goldston: What is your response to the criticism of the then Prime Minister Singh’s concern, that we hear from others as well, that you’re end-running around democratic representative government by going to the courts?

Gonsalves: We don’t have any hesitation about that. When governance crumbles, then the protection of human rights, of fundamental rights, is the fundamental duty of the courts. The court will tell the government, There’s a repeated violation of rights. Do you want to correct that? When there is, there is no iron wall between the executive and the judiciary. Once having given you the chance, then the courts will take over and say, The enforcement of fundamental rights is our duty. It’s not contrary to the separation of powers. It’s compatible even with a traditional notion of separation of powers. But the separation of powers doesn’t usually take into account the breakdown of governance, the crumbling of governance in the third world. That’s why western lawyers have made my life miserable, asking the same question again and again. [laughs] Do the courts abide by separation of powers which is cast in stone, or do they relieve the people and give them food and housing and education and welfare?

Goldston: Recognizing that Indians will determine the future of India, is there any role for the international human rights community?

Gonsalves: You can play a huge role. If you have something in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, The Guardian, India is very sensitive to what well-known people of reputation say about them. If lawyers band together across the world and monitor judges and judgments and comment fairly on what is happening, it would have a huge impact. Currently, the West is not committed to looking at what will happen in the next five years to the largest democracy in the world. The West used to be long-term planners, nation-builders, continent-builders after the war. Look how Berlin was re-constructed. Now you don’t have people like that, except perhaps for Merkel. You have people who are businessmen with one-year profits.

Goldston: How would you say, as you look back now, are you more or less hopeful about the power of litigation and law to achieve change in India. How does it compare today?

Gonsalves: I think it’s broadly the same as it was when I started, maybe a little bit more uncertain in view of the political developments. But that is not really the question I would put myself. It is, “Are you able to take people who are lawyers, or are training to be lawyers, and inspire them to dedicate their lives for the use of the law for defense?"

And if people are willing to do that in circumstances where success is less possible today than it was maybe five or ten years ago, that’s even better. It’s not really the success or failure that’s important; it’s inspiration. Someone who would speak to their hearts and set ablaze a little fire of rebellion. To be rebellious and bold and foolish, maybe and learn to speak out.