Raising the Profile of Pretrial Detention in Africa

By Marina Ilminska & Martin Schoenteich

A year ago, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights officially launched a new bid to improve the way that the criminal justice systems across Africa treat suspects before they go to trial. New standards, known as the Luanda Guidelines, deal with the conditions of arrest, police custody, and pretrial detention in Africa. They were adopted by the commission out of concern about the impact of prison overcrowding and the consequences of arbitrary arrest and prolonged pretrial detention in Africa. As part of the effort to raise the profile of this issue, April 25 has now been declared Africa Pretrial Detention Day.

The guidelines focus on the actions of criminal justice personnel from the moment of arrest until trial, covering issues such as arrest and custody, safeguards for arrestees and defendants, measures to ensure law enforcement transparency and accountability, and ways to improve coordination between criminal justice institutions. In particular, they seek to ensure fewer arbitrary arrests and more rational and proportionate use of pretrial detention.

As we celebrate the first anniversary of the launch of the guidelines it is fitting to take stock of the pretrial detention situation in Africa, recognizing that Africa is a diverse region comprised of 54 states with pretrial justice practices that vary significantly across the continent.

Despite substantial population growth over the past half century, and increases in crime fueled by urbanization and modernization, the capacity of African prison systems has hardly changed. As a result, many of the continent’s prison systems are in a state of crisis, burdened with overcrowding and an inability or unwillingness to protect the human rights of prisoners—a constituency which is marginalized and widely despised by politicians and the public alike.

Imprisonment rates are not particularly high in Africa. The continent has 15 percent of the world’s population, but only nine percent of its prisoners. Some African countries have particularly low prison populations. Nigeria, the most populous country on the continent with 179 million inhabitants, has 57,000 prisoners—about the same as the state of New York (pop. 20 million). The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with a population of 68 million, has an estimated 25,000 prisoners.

Yet, Africa’s prisons are overcrowded. Of the world’s 20 most crowded prison systems, almost half are in Africa. In countries as diverse as Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, Mali, Uganda, and Zambia, prisons hold between two and three times the number of inmates they are designed for, according to the International Centre for Prison Studies.

These apparent contradictory tendencies—low imprisonment and high crowding rates—are a consequence of weak state capacity, poor governance, and a myriad of pressing development needs which persistently sideline the modernization of criminal justice processes and expansion of prison infrastructure.

Weak state capacity undermines the ability of criminal justice systems to prosecute and convict most of the individuals who commit serious crimes. In addition, high levels of corruption allow many suspects avoid prosecution or conviction. A result—and a key driver of prison overcrowding—is the region’s unusual pretrial detention pattern.

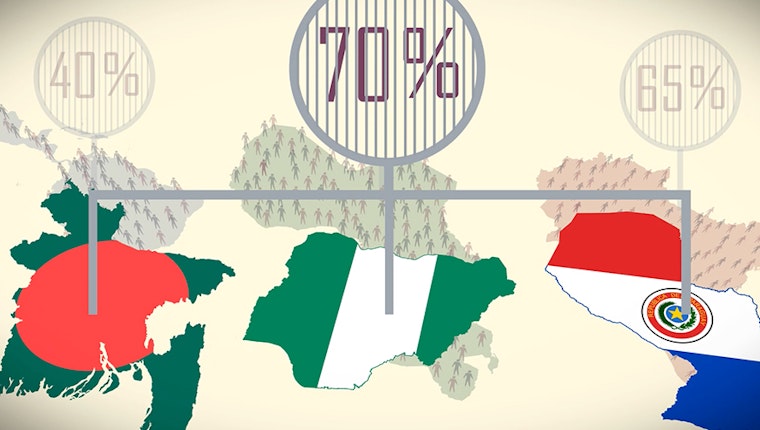

Globally, just under a third of all prisoners are pretrial detainees—persons awaiting trial or the finalization of their trial. It is close to 40 percent in Africa, and over 50 percent in Central and West Africa. Of the world’s ten prison system with the highest proportion of pretrial detainees, half are in Africa. In places such as the Benin, DRC, Liberia, Libya and Nigeria, 70 percent or more of all prisoners have not been convicted.

Prison systems with high pretrial detainee populations are characteristic of criminal justice systems with a dearth of investigators, prosecutors, judges and courts to expeditiously process arrestees through the criminal justice process. Moreover, in places where law enforcement is corrupt, arrests are motivated more by individuals’ ability to pay a bribe then credible evidence of criminal wrongdoing.

Violence, torture and related physical and psychological abuses of prisoners are particularly acute during the pretrial stage of the criminal justice process, typically to extract confessions from defendants. To the extent that pretrial detainees are segregated from convicted prisoners, the former are generally confined in worse conditions than convicted prisoners. Pretrial detention centers tend to be especially overcrowded, and pretrial detainees typically have little, or no, access to educational, vocational, and related work opportunities.

African states benefit from a plethora of regional standards and norms to guide the promulgation of rights-based national laws and corrections practices. Two decades ago, the African Commission established a special rapporteurship on prisons and conditions of detention in Africa, the same year as a group of African countries and civil society organizations adopted the Kampala Declaration on Prison Conditions in Africa.

In 2002, the African Commission adopted the “Robben Island Guidelines” which encourage African states to adopt minimum international standards on prison conditions. A year later, the African Commission adopted the Ouagadougou Declaration and Plan Of Action on Accelerating Prison and Penal Reform In Africa. Now we have the Luanda Guidelines.

The challenge for African policy makers is to incorporate regional standards and guidelines into national legislation and to ensure such statutes are implemented. The promulgation of good laws is a necessary step in the right direction. Crucial, however, is the sustained improvement of the day-to-day practices and bureaucratic routines of criminal justice practitioners and corrections personnel.

There are plenty of other special “issue” days already marked by AU members—all aimed at raising the profile of the issue in question. An Africa Pretrial Detention Day can help raise awareness of the need to align regional standards with national laws and practice. This is especially important in respect of pretrial detention. The right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty is universal, but a majority of prisoners in many African countries—and, indeed, elsewhere—are behind bars, awaiting trial. No right is so broadly accepted in theory, but so commonly violated in practice.

Marina Ilminska is a policy officer for national criminal justice reform with the Open Society Justice Initiative.

Until March 2021, Martin Schoenteich was a senior managing legal officer on national criminal justice reform with the Open Society Justice Initiative.