The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is Deploying a Massive New Database to Gather Biometric Information

By Lesley Nash

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has recently come under intense scrutiny. Its response to recent Portland, Oregon protests, which involved battering protesters and sequestering them in unmarked vans, illustrated just how disturbingly the nation’s largest law enforcement agency put Americans’ safety and civil rights at risk. The President’s moves to coopt the agency for political purposes—using it to enforce draconian immigration policies and crack down on protestors at home—has also raised alarm.

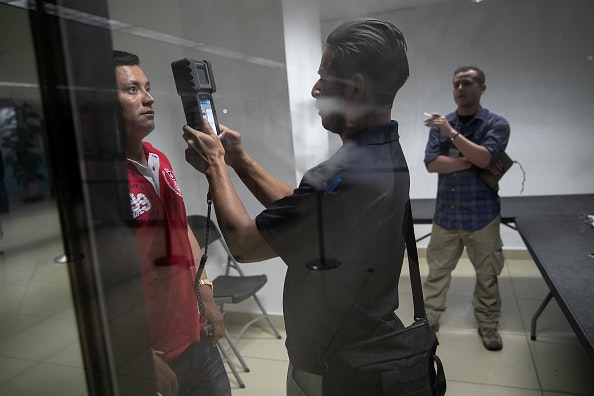

While these events have generated concern about the future of the DHS, something else has escaped headlines: how this government agency collects and shares data on individuals. Last year, DHS announced that its Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT), the central DHS-wide system for storage and processing of biometric and associated biographic information, would be replaced by the Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology System, or HART. HART, which could be deployed later this year, represents the covert ramping up of DHS’ surveillance and information-sharing functions—and will be one of the most alarming and excessively invasive tools the agency will have at its disposal.

While HART will contain all the information currently held in IDENT, such as photos or fingerprints, it will also include more biometric and biographic information on identifiers such as scars, tattoos, and even DNA. The HART system will also include law enforcement “encounter data” and information about “relationship patterns,” vague terms that raise concerns about just how far the agency will go in collecting data. HART’s unprecedented ability to store and search all data in a single location, under a single unique identifier for each individual, will make it much easier to gain a complete picture of an individual, even of those who have not engaged in illegal activity of any kind. This will contribute to the creation of a surveillance network that is expected to contain information on hundreds of millions of people by 2022.

Where data sharing has been limited by the capacity of DHS’ older systems, HART’s new infrastructure is intended to allow more and easier interoperability between itself and partner databases. DHS revealed in May that it would be sharing data with numerous other agencies, including the Department of Justice, the Department of Defense, and local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. DHS sub-agencies⸺including those that have gained notoriety due to their heavy-handed tactics, such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection⸺will also have access.

DHS and other major federal agencies, such as the Departments of Defense and Justice, are working to make their major databases interoperable, meaning that these databases will be able to—in the agency’s own terms—“communicate with each other seamlessly.” HART will ‑also have greater capacity for inter-database sharing and searches by other government agencies than its predecessor did, including with foreign partners such as Mexico’s National Institute of Migration, Guatemalan’s Ministry of Government Institute of Migration, the United Kingdom’s Border Agency, and the governments of Greece and Italy, among others.

Why should we be concerned? Think of it like this: HART sits in the middle of a data-sharing architecture like a spider at the center of its web, consuming and distributing a massive amount of data that will be shared between DHS and its state, local, national, and international partners without public scrutiny or democratic oversight. The existence of this surveillance architecture threatens both anonymity and free speech. HART will not only be used to identify violations of immigration or criminal laws. It will be an important part of a massive, over-arching surveillance and data-sharing architecture affecting us all. Misleading or outright inaccurate information may lead to increased surveillance, harassment, or detention of individuals without cause. Databases like HART are also likely to compound existing social and racial inequalities in policing and surveillance. Where groups are more likely to be over-policed or over-surveilled, their information is more likely to end up in a database like HART, potentially endangering their First Amendment rights⸺such as their right to protest⸺and threatening invasions of privacy.

While this would be troubling under any leadership, it is particularly concerning under the current Trump administration, whose policies pose a threat to Americans’ civil rights and the human rights of migrants. In a country that has seen increased surveillance, racial bias, and threats to constitutionally protected rights, HART and the other databases it is linked to represent the type of surveillance architecture that belongs in dystopian fiction rather than in the heart of American democracy.

Lesley Nash is a legal research intern at the Open Society Foundations Justice Initiative and is currently completing an LL.M. in Public International Law at the University of Nottingham.